Business Week

Business Week's April 10 issue had an

interesting story about the publishing industry moving toward an on-demand model. It's about time. Things have followed the same path for decades: the hardback comes first, followed a year or so later (depending on the success of the hardback) by the paperback. Audio and, lately, digital, fall somewhere in between.

Much like the music and film industries before it, the publishing world is slow to change and resistant to any alteration of the formula. It resists at its own peril. But help is on the way. The Caravan Project, pushed by Peter Osnos, the founder of PublicAffairs books, will use a MacArthur Foundation grant on a project that will involve publishing 24 books in five formats simultaneously during 2007. The formats are hardcover, digital, audio, print-on-demand and piecemeal.

It's an idea whose time has come, as people are quickly being trained to expect what they want now. Patience is something expected by an increasing number of boarded up businesses. On-demand is the future.

Critics argue on several points. An author is quoted as saying that he makes more royalties from hardback sales, while publishers worry about the "Napsterization" of their intellectual property. On the first point, how many sales are lost during the initial publicity push because people don't want to shell out $25 for a book they may or may not like? Offer those who simply want to read -- not just acquire a durable status symbol -- the chance to pay $12 for a book, or event $1.99 for a relevant chapter. As for the second point, should publishers really be worried about people taking illegal steps to obtain reading material? Napster and other file-sharing services can impact the sale of music and movies because those are things people actually want to buy. It's not as if people ever line up to buy a new book the same way they do to buy a CD from the latest chart topper or a ticket to the latest Hollywood blockbuster. Besides, reading anything longer than a magazine article online or off in digital form continues to be tedious. The lost revenue from such theft will be minimal.

The upside, as I alluded to above, is that publishers need only market a book one time. No need for the secondary paperback push. This can result in increased sales, of course, as people are reintroduced to something. But too often, particularly for non-fiction titles about current events, something better will have come along by the time the paperback hits the street.

This won't happen quickly or quietly, but it will happen.

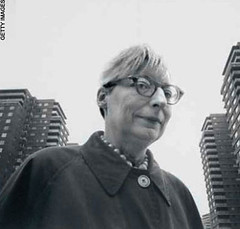

Jane Jacobs, whose thoughts and writings on the urban landscape and metropolitan diversity still resonate in the works of admirers like Richard Florida, died today. She was 89. Though best known for her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs continued to work and write, penning the cautionary tale Dark Age Ahead in 2004.

Jane Jacobs, whose thoughts and writings on the urban landscape and metropolitan diversity still resonate in the works of admirers like Richard Florida, died today. She was 89. Though best known for her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs continued to work and write, penning the cautionary tale Dark Age Ahead in 2004.